Autism & Wandering: It Happens in Every Community

By Camille Proctor, Color of Autism Foundation

In 2006, I gave birth to a beautiful little boy name Ari and fell in love. Two years later, Ari was diagnosed with autism and exhibits many of its unique behaviors. One such behavior is “wandering,” one of the most frightening behaviors of all.

In the summer of 2008, Ari slipped out of the home while I was using the restroom. Once I realized he was gone, I ran out of the house frantically calling for him. I remember it was raining and a car pulled up. Thankfully, it was my neighbor with Ari and my dog, Boo. She found Boo (who I didn’t realize was missing) sitting on top of Ari on the grass on the other side of the cul-de-sac. I was so grateful to my neighbor for rescuing my son. I was equally grateful to Boo for her instinct to protect and follow Ari. Not knowing that wandering was associated with autism, I shrugged this incident off, not expecting it to re-occur.

The next incident happened in the spring of 2009 when Ari turned the lock on the door that led to our garage, pressed the garage-door button, and bolted. Once again Boo sprung into action and caught Ari a few feet away from our home. The most recent incident was in the summer of 2010. I was taking groceries out of my car when Ari crawled out the hatch-back and ran toward the exit of my gated community. This time a neighbor brought him home and scolded me for being a “bad parent.” Another neighbor told me I needed to get Ari in check, a second neighbor just shook her head, and a third showed us compassion. I thanked them, and became very upset because the two reprimands I received were from my African American neighbors accusing me of bad parenting and the only person that seemed to understand was white. A few weeks later I saw my African American neighbors who supplied the unsolicited advice and I again thanked them for saving Ari. I tried to explain that Ari has autism and wanders. I was met with opposition and was told that “black” kids don’t wander.

The reality is that any child can wander and that “any” includes African American children. Ari hasn’t wandered off since 2010, but there’s still a very high likelihood that he may attempt to wander again. Our home is equipped with door alarms and sensors. The threat of wandering will always be present, and while Ari has been swimming since age two, he’s no match for a strong water current. He also lacks the safety skills to avoid other wandering-related dangers like oncoming traffic.

As parents, our job is to protect our children and keep them out of harm’s way. As advocates, we must spread the word in our local communities, educate, and do everything we can to help protect our most vulnerable citizens. I didn’t know wandering could happen. And according to a 2012 study in Pediatrics, I’m not alone. Only 50% of caregivers reported receiving advice or guidance from a professional on how to prevent wandering. You can be certain that number is much lower in underserved communities. So let’s get out there and do our part to reach every caregiver with this vital information. It just may save a life.

For ways to prevent wandering, visit http://awaare.org or http://autismsafetycoalition.org/find-resources/.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

ABOUT AUTISM-RELATED WANDERING

Similar to wandering behaviors in the Alzheimer’s community, wandering and elopement behaviors in children and adults with autism have led to countless tragedies across the country.

A 2012 Pediatrics study showed that 49% of children with autism attempt to elope from a safe environment, a rate nearly four times higher than their unaffected siblings.

It also found that more than one third of children with autism who wander/elope are never or rarely able to communicate their name, address, or phone number. Two in three parents of elopers reported their missing children had a “close call” with a traffic injury. Thirty-two percent of parents reported a “close call” with a possible drowning. Wandering was also ranked among the most stressful autism behaviors by 58% of parents of elopers. Half of families with elopers report they had never received advice or guidance about elopement from a professional.

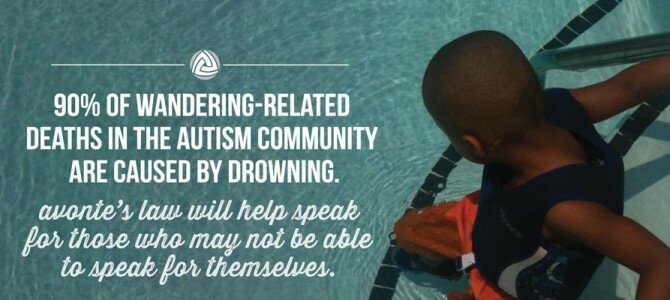

According to the National Autism Association (NAA), accidental drowning accounts for approximately 90% of wandering deaths reported in children with autism, with a strong majority of deaths happening in a nearby pond, lake, creek or river. NAA also found that 42% of wandering cases involving a child with autism 9 and younger have ended in death.

Wandering is typically a form of communication — an “I need,” “I want,” or “I don’t want.” Someone with autism may wander to something of interest, especially water, or away from something that is bothersome, such as uncomfortable noise or bright lights.

Children and adults with autism wander from all types of settings, such as schools, residential homes, camp programs, public places, and home settings.

Wandering and elopement tend to increase in warmer months, especially in mid-section areas of the US where home layouts and routines are adapted to accommodate changing weather. To learn more about wandering, visit http://awaare.org.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________